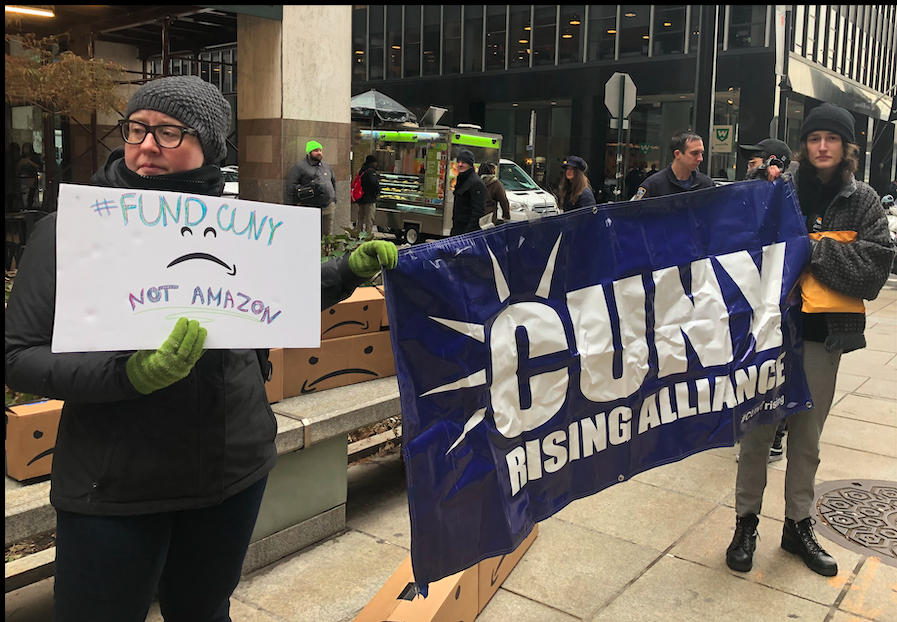

Hunter and CUNY students and faculty across the city have banded together to protest the university’s partnership with Amazon, which plans to develop a large new campus in Queens. They have taken to the streets to protest any connection CUNY will have with the corporate giant, to which the city and state have offered tax incentives in exchange for bringing new jobs.

“I felt horrified,” said Carlos Calzadilla-Palacio, an undergraduate at Brooklyn College and president of the Young Progressives of America. “Seeing [CUNY Board of Trustees Chairman] Bill Thompson endorse this deal was insane to me, and was immoral. And I realized that we have to fight back.”

Last month, Vita Rabinowitz, interim chancellor at CUNY, and William J. Thompson, chairman of the CUNY Board of Trustees, announced that CUNY would commit its “considerable college assets to ensure that Amazon has a strong pipeline for talent, ideas and innovation.” Rabinowitz said that CUNY “stands ready” to help “provide skilled graduates ready to compete for Amazon’s 40,000 new jobs.”

Although there are few details about the partnership, soon after the announcement, student groups began organizing against it. Hunter College’s Coalition for the Revitalization of Asian American Studies (CRAASH) shared a petition called “Keep CUNY Out of Amazon” on social media that received nearly 400 signatures. CUNY activists put together a zine giving reasons to oppose the Amazon deal, and there is now a Facebook page called “CUNY Not HQ2,” citing the slang name for Amazon’s new headquarters.

Following their announcement, Thomson and Rabinowitz co-authored an op-ed in the Daily News praising the partnership for its ability to help students of different socioeconomic and immigrant backgrounds and diversify the tech field. With programs preparing students to work in STEM fields, CUNY is a “natural collaborator in the establishment of Amazon’s on-campus public high school,” they wrote.

But the op-ed only further fueled student anger.

“We’re demanding that Chairman Thompson rescind that op-ed and his support for Amazon, and that these billions of dollars in tax breaks going to Amazon actually go to CUNY funding,” said Calzadilla-Palacio, who helped organize a protest with the CUNY Rising Alliance in late November. “And we are also rejecting this deal in general of Amazon coming into New York.”

Opposition towards the partnership broadly stems from issues students have with Amazon as a company, the gentrifying effects that the headquarters may have on communities that students come from, as well as more specific frustrations that Amazon is receiving as much as $3 billion in financial incentives while CUNY stays underfunded.

Corinne Greene, president of the Brooklyn College chapter of Young Progressives of America, called the company “unethical” and said the state should not be giving tax breaks to Amazon at all.

“And definitely not before funding CUNY first,” she said.

However, the issue of whether incentives for Amazon could have been used for other funding priorities like CUNY is complex.

“Ultimately if you’re giving out these benefits it does reduce the amount of revenue that otherwise would be available for other services,” explained Sean Campion, a senior research associate at the Citizens Budget Commission, a nonpartisan organization that published an analysis of the Amazon deal.

However, he said the narrative that the city and state are giving $3 billion to Amazon instead of other priorities is “an oversimplification.”

Most of the incentive package is not money given upfront to Amazon, but rather, breaks and credits on its tax bills in the future—and not money that could have been spent elsewhere. In other words, despite the tax breaks, Amazon will generate tax revenue for the city and state that would not have existed otherwise and could be spent on other priorities, the city and state have argued.

However, the incentive package also includes millions in grants, which is money paid directly by the state, rather than breaks on future revenue. For instance, according to the Citizens Budget Commission, the Empire State Development Capital Grant will reimburse Amazon for capital costs of its office buildings at a maximum of $480 million, as well as $505 million for the costs of site preparation and infrastructure improvements.

The funds for this grant, Campion explained, could have potentially been set aside for other programs.

“This is sort of a broad appropriation… in the state budget that didn’t necessarily have specific projects tied to it,” he said. “It’s sort of a pot of money that they control for projects like Amazon.”

Even then, the issue becomes more complex. The state is not simply paying the grant upfront—Amazon will only receive the money if they meet certain conditions that produce revenue. For instance, Amazon will receive up to $325 million from this grant if it creates 25,000 jobs. The grant will be paid over the course of 15 years.

Governor Cuomo recently said that the state would gain revenue in the long run at an estimate of nine times the subsidies. His math was based on an economic impact study sponsored by Empire State Development. But Campion said current estimates of public return on investment are not that simple, as they haven’t factored in expenses, alternative uses of the site, and what might have been built if Amazon did not move into Long Island City.

The bottom line is that the tax incentive package is complicated, and to some degree, politicians and opposition groups alike have oversimplified the issue.

Economic arguments aside, protestors’ ethics complaints remain. It is true that Amazon has met with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency to sell facial recognition technology, which puts CUNY at odds with its touted goal of supporting undocumented students. Amazon’s new headquarters could also drive out low-income families, many of whom CUNY students come from. Housing costs in the area have already started to rise as a result of the deal.

In its petition, CRAASH expressed this concern, saying, “CUNY administration thinks it’s okay to support and send students into a company that exploits its workers and helps ICE, police, and law enforcement to identify and surveil people and develop facial recognition technology rather than genuinely seeking to protect and support undocumented students.”

Since CUNY’s announcement, student opposition has extended beyond social media and onto the streets. In late November, students rallied outside Thompson’s office, and a week later, CRAASH protested at a Board of Trustees hearing at LaGuardia Community College. At the hearing, two members tried testifying about the Amazon partnership, until a trustee said the item was not on the agenda. When the protesters refused to stop talking, he turned off the mic and the board called a recess, walking off stage as a group of students started chanting. Rolling out a banner reading “CUNY Not HQ2,” they walked to the back of the room in protest.

At a board meeting on Dec. 10 Thompson said individuals could testify about Amazon at a hearing on CUNY’s budget proposal that will be held at a future date.

CUNY faculty have also joined the chorus of opposition. Many members of the Professional Staff Congress, the union representing over 30,000 CUNY staff and faculty, view CUNY’s support of Amazon as “a betrayal of the university’s mission by turning it into a vocational school and a pipeline to an unaccountable private business.” On the union’s website, President Barbara Bowen said, “The key issue is the giveaway of public resources to the world’s richest company – one with a horrible labor record. Billions in state resources are being handed over to Amazon while CUNY is being starved of funds.”

The city has estimated that the Amazon headquarters, which will be located along Anable Basin in Long Island City, will generate $27.5 billion in revenue over 25 years and 40,000 jobs by 2034, with an average salary of $150,000, according to Amazon’s press release announcing the new headquarters.

But some of the protestors think it’s unlikely those jobs will actually go to CUNY grads.

“They’re not going to hire CUNY students,” said Calzadilla-Palacio. “They’re not even going to make a commitment to do that. These are going to be people with six-figure jobs moving into this community and displacing so many people.”

Hercules Reid, who serves as legislative director of the University Student Senate, says the university can’t expect student support unless they see and understand the details of the partnership.

“What are we actually getting?” he asked. “What internships are going to be available? And how much of that revenue is going to go to our buildings that are falling down, to the tuition that continues to rise to cover the operating costs?”

In the meantime, student activists are determined to pressure CUNY into rescinding the partnership. CRAASH recently tried protesting at a Board of Trustees meeting held on Dec. 10 and showed up again at a Town Hall meeting with Mayor de Blasio at Hunter on Dec. 19.

At the town hall, Jennifer Raab, president of Hunter, called de Blasio “a visionary in seeing New York City as Silicon Alley.” She added that Hunter participates in a city program called CUNY 2x Tech, an initiative to double the number of CUNY students graduating with a tech-related degree by 2022.

“These will be students who are of color, women, new immigrants, who will be able to take the jobs you’re bringing here with Amazon,” she said, before asking de Blasio to renew the program for another two years.

Despite administrative support for the partnership, Greene, a three-generation public school student whose family has deep roots working in public education, remains hopeful that students can make their demands known.

“Students have been on the forefront of major change throughout American history,” she said. “So I don’t think it’s a radical notion at all.”