The sun is fully set behind the large windows, most of which are fully covered with beige shades. There’s a comfortable silence embracing the classroom of barely 10 people; a couple more will trickle in a few minutes before seven. The professor stands in front of the whiteboard, squeaky black marker in hand as he marks up random words and diagrams.

He wears a green jacket over a button-up, alongside a pair of dress pants. Though the seasons keep getting progressively warmer, he never takes off the thin jacket or wears anything in deviation from this uniform. As he raises his hand higher, filling up the empty space of the whiteboard, black ink decorating his skin peeks out of his jacket cuff. It spans from his wrist, presumably somewhere higher up.

Sometimes when he walks in, he stuffs a blue mask in the upper pocket of his jacket. The only thing that indicates where he has been a few hours before.

When the clock hits seven, he turns away from the board, or puts down the book he was reading, and stands casually in front of the podium.

“So, what’d you think of the reading?” he casually says.

The Happenstance of Studying Religion

Brian Foote works as a chaplain at Weill Cornell Medicine during the day and teaches Witchcraft and Religion during the evening. He wasn’t always a fan of religion, or even considered it as a professional pathway.

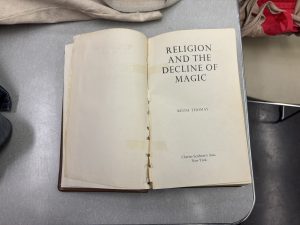

Foote grew up in a small evangelical town in Texas, where he found himself (and his family) different from the average person living there. He recounts his experience growing up there as uncomfortable, if not dangerous. One of those instances was when Foote and his family ended up being used in a strange video made by the local church to call people to Jesus and away from sin. All it took was Foote allowing an ex-girlfriend to borrow his father’s book about natural magic, without thinking much of it. Somewhere down the line, information about the book reached a teacher at Foote’s highly religious old high school, which he had already transferred out of, who relayed it to the church. Some legal threats were made, and the video was taken out of circulation.

His negative experience didn’t dispel him completely from religion, though. Foote was getting his bachelor’s at Hunter, with a focus on pre-law, when he took a Faith and Disbelief class taught by Barbara Sproul to fulfill an elective credit.

“It was the most interesting thing I had ever done,” says Foote. “The material was not at all what I expected.”

So, he took another class, and another, and eventually became a religion major. He says it was complete happenstance, but it worked out for the best, especially when he got into Harvard’s Divinity School for his master’s. The experience was gratifying, but he didn’t jump into teaching straight away.

Life circumstances and his financial situation led him to, surprisingly, a job in finance. Though it made good money, it didn’t satisfy Foote as he yearned for a career in teaching, something more closely related to religion. However, deeply saddening family circumstances got hold of him. Foote’s mother got sick, and then his brother, Charlie, got brain cancer.

While Charlie was sick, a part of his care was receiving chaplaincy services. Charlie was an atheist, but the chaplaincy care he was provided was not tailored to his beliefs and needs.

“He got really poor spiritual care for somebody whose illness was gradual and then sudden. [His health] went poorly, really quickly,” says Foote. “Watching him not get the full breath of care that he needed, I felt like, man, he really deserved better than that.”

This experience made Foote realize that he can be the one to plug that gap for others in similar situations.

“When you see a problem, you can’t just complain about it,” says Foote.

So, he got a severance package from his job and took up his friend on an offer to be a teaching fellow for a Social Determinants of Health class at Harvard. Foote’s teaching career took off then. After his teaching fellowship, he came back to Hunter as a professor.

Then the pandemic happened, and chaplaincy became more needed than ever. Foote enrolled in chaplaincy training while teaching religion at Hunter, balancing both things when the state of the world was uncertain and terrifying.

“Growing up in Texas, there was a phrase–riding two horses at once, which is like a rodeo trick. For a long time now, I’ve been riding two horses at once,” says Foote.

Foote was an intern during the pandemic, so he was protected from a lot of the brutality of sickness and death in the hospital. By the end of the worst of COVID-19, Foote was mostly there as support for staff rather than the patients. The pandemic completely wrecked the nurses, primary physicians, and anyone on staff who were on the frontlines. They were completely burnt out, if not scarred from the amount of time they spent in the presence of death.

“Everyone at Cornell talks about it like it was wartime for them, and I don’t think they’re being hyperbolic,” says Foote.

Witchcraft and the Lack of Magical Culture

Now, Foote is teaching during another, though different, unprecedented time when young people are the ones in need of guidance. Witchcraft and Religion is a new addition to a list of courses Foote teaches. His usual rotation is Religion and Healing, Religion and Psychology, and introduction level religion courses.

Witchcraft and Religion might sound intimidating, but the class mostly deals with power structures and the role of witches in society.

“What do we do with this concept of a witch? More importantly, who has the power to determine who is a witch? At some level, at heart, all my classes are ultimately about power structures and who actually gets to navigate the levers of power in society,” says Foote.

Foote finds the practice of magic culturally fascinating. He believes that magic is a very overlooked part of society, specifically how it relates to human ingenuity and our ability to find ways to regain control in situations where we’re powerless. Ultimately, that’s the point Foote is trying to get across with this class. Who practiced magic and why? And how did the people in power treat them? Oftentimes, magic and witchcraft were helpful tools for those who were oppressed or faced general unfavorable circumstances.

“We’re not really a magical culture anymore. I worry about it,” Foote says, contemplating.

Foote is a Buddhist, but he strays away from discussing his personal practice in his classes.

Though Witchcraft and Religion had a great running start this semester, it’s unlikely that it will make a return next fall. The demand from the students is simply not there; a saddening turn, especially during the current political climate.

The class itself came about in an interesting way. Wendy Raver, the director of the religion program, was looking for ideas for new class offerings, which often happens by going through old syllabi of inactive classes. That’s how they stumbled upon a syllabus of a witchcraft class from the 80’s. Coincidentally, during that time Foote was sorting through archival records at Cornell, and found one about a loosely organized group of young Wiccan practitioners who worked on hexing the Trump administration, during Trump’s first go around. He felt like the class would be worth reintroducing to Hunter students, and Raver agreed.

Foote greatly cares about his students, which comes through in the way he speaks about what he wants students to remember from his classes.

“You are the authority in your own life for your own meaning-making process. You’re not just an agent of other arms of power. Who are you? What is your life actually about? If you don’t spend your life investigating that question, then somebody’s gonna figure it out for you,” says Foote.

The Student Perspective

His care is not just seen in his words, but also felt by his students in his Witchcraft and Religion class. Julia Matlak, an English and biology major, recommends the class to others and praises Foote’s approach to teaching.

“One of the things I most admire about Professor Foote, besides his wonderful intellect and his interdisciplinary approach to this class, is just how much he respects students and their perspectives. He makes the classroom a collaborative environment and never shuts anyone down,” says Matlak.

Franny Lopez Hernandez, a studio arts major, couldn’t agree more.

“His teaching style is really about informing the next generation and encouraging us to use our critical thinking skills. It is truly magnificent to see that kind of commitment to educating the future generation, especially in this political climate,” says Hernandez.

Maybe young people should take into account Foote’s worries about the lack of magic and celebration of human ingenuity in today’s culture. Connecting to one another, learning from the past, and acknowledging one’s autonomy in a world seeking to strip it away can be a magical experience.