I really don’t like the movie Gummo, Harmony Korine’s gung-ho, mostly plotless, home movie-tinted ode to impoverished America. I find the film exploitative, generally unpleasant, and boring. (I recently watched the film again to make sure my opinion held up. It did.) I bring up my opinion of Gummo because Korine’s follow-up feature, Julien Donkey-Boy, is a very similar film in style, only this one has more identifiable main characters and even less plot. Critics savaged Gummo when it came out, and gave Julien Donkey-Boy similar treatment. Gummo has a lot of fans, including noted film directors, but I’m squarely on the side of the critics. So why do I like Julien Donkey-Boy?

Whereas Gummo had mostly non-actors from dark corners of Nashville, Harmony puts recognizable people front and center this time, including Gummo superfan Werner Herzog, and Trainspotting’s Ewan Bremmer in the titular role. Julien is a fast-talking, hyperactive schizophrenic. His sister is pregnant. His brother’s into wrestling. His father is tough on him because he wants his son to be a winner. They live in Queens. Julien hangs out with people with disabilities. And…that’s pretty much the whole movie. There’s no real plot, it’s just a series of vignettes involving the family, all shot through a shakily-maneuvered standard-definition digital camera. Actually, shot through a digital camera, then converted to 16mm film….then converted to 35mm film. The resulting image is very grainy and oddly-colored, giving the film a unique, deliberately terrible look, and that’s already assuming that it’s a scene where Harmony isn’t shooting with lower-quality cameras or filming what he’s shot off a television screen. It’s possible to see the film’s caution-thrown-to-the-wind cinematography as helping to put the audience in Julien’s kinetic mindset, or as presenting the film as a series of dysfunctional home videos. In addition, the film opens with a certificate saying that the film was produced under the guidelines of the Dogme 95 movement. One of the guidelines is that the camerawork must be handheld, and many films produced under the movement have similarly shaky camerawork. However, since Harmony appears to have ignored every other rule in the Dogme 95 guidelines while making this film, I’m not going to consider the movement in regards to his cinematography. I honestly have no idea why that certificate is even there.

Julien Donkey-Boy is among the first films to be shot digitally, and it’s fascinating to see Korine take advantage of new technologies at such a young point in the medium. Scenes are shot a low frame rates using delayed exposure, giving everything a blurred, hallucinogenic look. Editing is rapidly-paced at times—to the point where one scene is entirely made up of half-second shots. His MiniDV camera can be maneuvered with ease, which he demonstrates with his frenetic cinematography. Digital video seems freeing to him, and the audience gets to witness him try out the tools he now has at his disposal.

One of my major complaints about Gummo was that I believed it used legitimately marginalized people to create a sideshow-freak aesthetic. While I admire Korine for giving such people parts in his film, it felt exploitive. Despite Julien’s recognizable main cast, many of the film’s supporting players are non-actors with physical or mental disabilities. Julien spends portions of the film at what appears to be a facility for people with disabilities, and there is a real sense of community among the residents that Gummo’s cast lacked. I really felt for Julien when he joins everyone in dancing at a birthday party with the others at the facility. There’s a sense of genuine warmth in this scene that is surprisingly not diminished by the fact that there is an extended sequence of a performer at the party eating several cigarettes and bringing them back up to smoke them. Also, Herzog plays cards with a man who has no arms, and therefore does everything with his feet. As this is a Harmony Korine film from the 90s, we are supposed to accept these events at face value.

This brings me to an aspect of the film that has always intrigued me, which is that I’m not sure how much of it is staged. Many scenes in this film are shot and played out as if Ewan Bremmer went to certain public locations and acted like a schizophrenic. A lot of scenes in this film are shot like a hidden camera show, with the cinematographer shooting from a distance as Ewan improvises. This is especially curious in what I can loosely refer to as the film’s climax. Julien’s sister has just given birth, but the baby was stillborn due to an ice-skating accident. Julien takes the baby’s corpse and brings it home with him. (It’s heavily implied that Julien is the baby’s father.) What follows is a scene of Julien getting on a Queens bus with the dead baby as people look at him in confusion…and it doesn’t look like acting. The video quality is noticeably lower as well. It’s feels like the world’s darkest episode of Candid Camera.

While we’re on that subject, I’m not sure what the overall tone of the movie is. In one scene, Julien fantasizes about getting a call from his mother, who died in childbirth. She says that she’s a dentist in the afterlife and gives Julien tips on dental care. It’s rather absurdist for what should be a heart-wrenching moment. Plus, there’s Werner Herzog. Oh boy, is there Werner Herzog. He walks around the house with a gas mask on for no reason. He tries the string from the Venetian blinds around his neck and opens and closes the window by moving his head back and forth. He calls a stream-of-consciousness poem Julien created “artsy-fartsy,” before describing the “Do I feel lucky” scene from Dirty Harry at the dinner table with the reverence of an art film critic. It’s utterly hilarious. What exactly is Harmony going for here? A wrenching but heartfelt and funny portrait of a dysfunctional family? A rather politically-incorrect prank film? An excuse to have people just do random stuff in front of a video camera?

Maybe there was a reason Harmony made this a Dogme 95 film. The Dogme 95 manifesto said that directors were no longer artists, and set out to tell interesting stories while showing life as it really was. Maybe Harmony, 26 and already considered either the art house’s biggest pariah or a misunderstood genius, was trying to capitalize on a new and interesting film movement. Or maybe he considered this film a story of life that nobody else filming in New York City wanted to tell. A story of the marginalized and forgotten in the biggest city in the country. It’s rare to see something like this and Gummo released by a studio like Fine Line Features, a division of a major Hollywood studio and media conglomerate, and I haven’t seen much like it since. Harmony, meanwhile, seems to have moved on in the past few years. His latest film in his surprisingly-short oeuvre, The Beach Bum, was his first to receive a major theatrical opening, while his previous film, Spring Breakers, was his first major release in general. I guess he got tired of being “artsy-fartsy.”

Side note: Metrograph preceded this film with a selection of two music videos and a commercial directed by Korine. The first features Bonnie “Prince” Billy’s No More Workhorse Blues set to a video of an African-American man with literal dollar-signs in his eyes and a woman in a bridal gown and blackface. The two do various activities, which are all shown in loops of a few frames each. The other video was for Living Proof by Cat Power, with a slow-motion scene of a high-school track meet where a woman is running with a cross on her back, with the other runners dressed in hijabs. They felt like videos from a karaoke machine you’d find in your dreams (or nightmares, particularly in the former video). An ad for Thornston’s chocolate uses similar visuals as the Workhorse video, with a young boy contemplating while people around him seem stuck in brief by repeating moments of time. Everything returns to normal when the boy realizes what wants–he was writing down something to be put on a personalized piece of chocolate. Harmony’s attitude towards promotional materials is that he knows he’s been commissioned to sell something, but nevertheless remains true to his experimental vision, if not fond of using controversy to attract eyes. Much of the Metrograph audience were amused when the final clip turned out to be an ad for chocolate–although I’m not sure what anyone would have initially thought that ad was for based on the imagery. I just hope Bonnie and Cat had seen Korine’s work before they hired him.

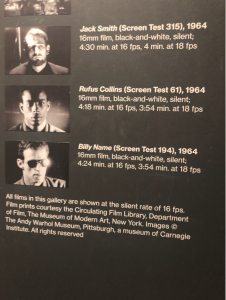

Andy Warhol: Screen Test 315, 61, 194

Andy Warhol: Screen Test 315, 61, 194

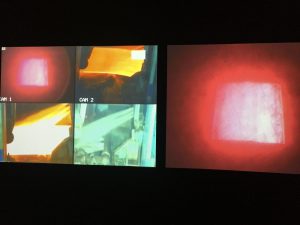

Mark Leckey Made in ‘Eaven

Mark Leckey Made in ‘Eaven